Delayed Irrigation in Walnuts

Authors: Kari Arnold, Ken Shackel, Bruce Lampinen

Water is flowing into the canals in Stanislaus County and growers are starting to turn on the irrigation, but is this necessary? Recent research by UC Davis and UC Cooperative Extension is showing that walnut trees may not need irrigation as soon as we might think. The use of a pressure chamber is changing the way we think about irrigation.

Moisture is lost from the soil either by direct evaporation from the soil surface (particularly right after irrigation) or by plant transpiration (uptake by roots and evaporation from leaves). Once the canopy shades the ground however, even right after irrigation when the soil surface is wet, the vast majority of water loss is due to transpiration. Additionally, this large amount of water lost during transpiration is when leaves are present. Although trees do transpire during dormancy through lenticels (raised pores in the stem of woody plants that allow gas exchange), the amount is extremely low. Because of this, very little moisture is lost from soil during the dormant months unless a cover crop or weeds are present, but even in that case, the root systems of cover crops and weeds are not as deep as those of walnuts or other trees/vines.

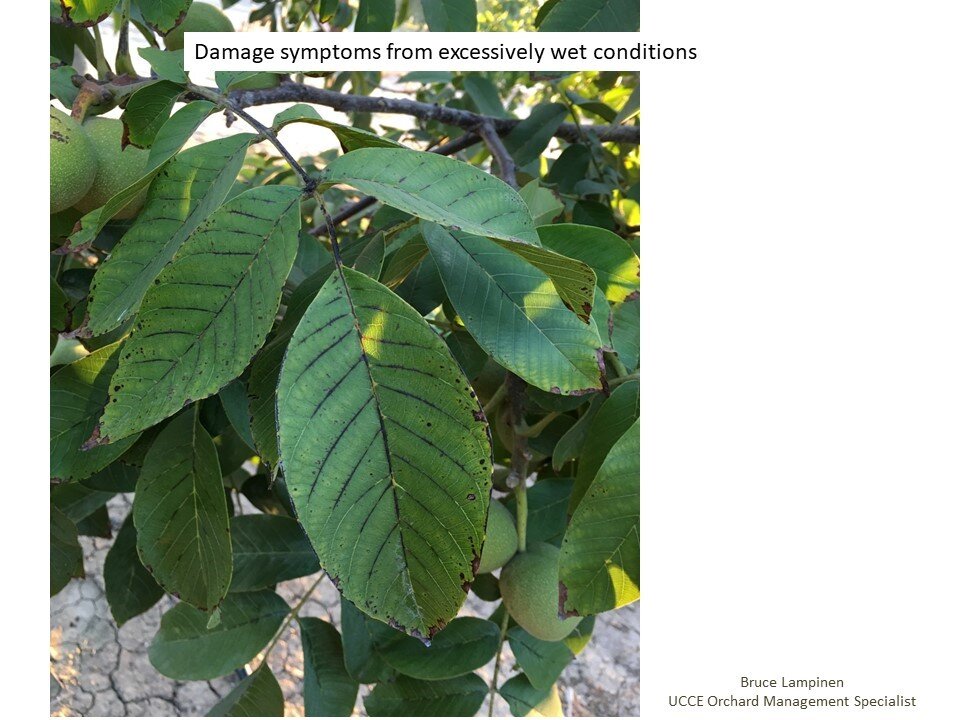

Some believe early irrigation is necessary to fill the soil profile in the spring and push the water down deep. This may be detrimental since trees are not utilizing the soil moisture yet in great capacity. In fact, trees irrigated early in spring tend to show stress symptoms later in July and August. Walnut trees tend to perform better when deep soil moisture is depleted throughout the season. Please see the following photos for over-irrigation in walnuts.

Recent research looking at delaying irrigation until trees read a certain stem water potential rating suggest a potential for healthier trees, without a detriment to yield. So, what is stem water potential? To answer that question, a discussion of basic plant physiology is required. Water moves from the soil to the atmosphere through plants. Plants, or walnuts in this case, suck water from the soil, utilize some for photosynthesis (a process by which plant cells convert light energy into chemical energy) as well as nutrient transport and cellular turgidity, but eventually lose the vast majority (over 95%) to the atmosphere when stomates are open. Stomates are like very tiny doors on the underside of most leaves, that open to allow carbon dioxide in (for sugar production, via photosynthesis), and oxygen out (a by-product of photosynthesis). While those stomates are open, water evaporates from the leaf, but this water is not being ‘wasted.’ It is the ‘cost of doing business’ for a leaf. The doors to the photosynthetic factory need to remain open for the factory to be productive. In addition, this water must be pulled by the leaf with a certain level of suction (negative pressure). The term stem water potential, or SWP, measures this suction and provides a window into how much water stress the walnut tree is experiencing – more suction means more stress.

Photos of over-irrigation in walnuts.

SWP is measured during the hottest, driest periods in the day when the tree is under the most stress, typically between the hours of 1:00 pm and 3:00 pm, although in some cases this might be as late as 3-4 pm. Leaves are folded inside mylar bags which are typically provided with the pressure chamber, and available in multiple sizes, although the smallest bags tend to fit the chamber best. The terminal leaflet of an interior walnut leaf is bagged and allowed to hang enclosed for at least 10 minutes. During this time, the tension of the water in the leaf becomes equal to the tension of the water in the tree. For most trees the best leaves to measure are on branches closest to the trunk in the lower canopy. The idea here is to reduce the distance from root to shoot so that the value properly represents the tree. The further away from the roots (and the more exposure to the sun), the more variable the value becomes. The stem of the bagged leaf is then inserted into the top piece, tightened down, and the stem is cut flush with the chamber top with a sharp razor blade (be careful!). The top is tightened down by either a clockwise motion for screw top models, or sturdy push pins provided in box chamber models, and pressure is applied either by pump action, or nitrogen gas canisters. Pressure is applied until a small amount of fluid is excreted from the cut stem. Always read all safety precautions and perform safe practices when operating this equipment. The value shown on the dial is recorded, and compared TO BASELINE, which is the most important, and often easily misunderstood, part. Baseline is a value that generally represents a fully irrigated tree. This value varies depending on the crop, relative humidity and temperature. Please see table 1 provided for walnut baseline values and directions on how to use it.

Trials are ongoing in both Stanislaus and Tehama counties. In Tehama four treatments are being compared. Initially the control, or the grower standard, was to keep trees irrigated according to evapotranspiration recommendations. The other treatments are delay treatments, with varying levels of stress being the trigger point to start irrigation, defined by stem water potential readings: one, two or three bars below baseline on a given day, consistently measured for a few days. Only the four bars below baseline treatment shows a significant drop in yield meaning one, two and three bar stress levels are equally comparable to the grower standards. After the first year’s observations, the grower decided to cut back the irrigation on the control treatment because trees appeared healthier in other treatments (delay treatments). In Stanislaus, two treatments are being compared. The grower standard irrigation time is triggered by the recommended number given by a soil moisture meter at an 18-inch depth. The second treatment is delaying irrigation until the trees read two to three bars below baseline. Additionally, trees which were declining in the orchard in Stanislaus County are now recovering in the delay treatment.

When should we begin irrigating? If you have a pressure chamber, use it. Read the trees and only irrigate once the trees have reached at least one to two bars below baseline. You know your field better than anyone else, if you have an area that tends to behave differently from another, you should check both areas in terms of SWP. Yet you do not need to read every tree, just a few per block depending on the variability in your field. Feel free to contact your local UCCE farm advisor for information. For a how-to video on using a pressure chamber, check out this video from Dr. H2O himself, Ken Shackel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M6ZkmB1ld60

Some of this information is also available in a separate article, “Declining walnuts, what’s the deal?” which is posted on this website and available in the September, 2018 issue of West Coast Nut.

Table 1. Baseline values for walnuts. To use, access the temperature (in °Fahrenheit or °F) and relative humidity (percent or % RH) for your location at the time of the reading (1 pm to 3 pm). Find the temperature on the left side of the table, then follow that line over to the corresponding relative humidity. The value inside the box is the baseline for walnuts at that given temperature and relative humidity. Keep in mind the baseline value is negative, and the pressure chamber value is negative; therefore, two bars below baseline will be two numbers more negative than baseline. For example, follow 64°F on the table over to 30% RH, baseline -3.7, therefore one to two bars below baseline would be -4.7 or -5.7, respectively, which would be a good time to irrigate. If the trees read -1.7, this would mean that these trees were above baseline, no need for irrigation.

Read a few trees in the block and take the average of those trees for comparison to baseline. Avoid reading edge trees due to edge effects.