Spur Pruning and Minimal Pruning on Raisin Grape

George Zhuang, UCCE Fresno County

Facing low prices for raisin grapes in the San Joaquin Valley, growers are being forced to make some very difficult decisions. Traditional cane pruning has a higher labor cost than other pruning methods. To save costs, I have witnessed Thompson vineyards being pruned in two different cost saving methods. The first is when the vineyard undergoes spur pruning (Image 1). I have also witnessed growers going in the exact opposite direction and using minimal pruning techniques on a few Thompson vineyards (Image 2). Continued low raisin prices might prompt growers to skip production this season with 2-node spur pruning to hope for a better price and a large crop for the following season. Minimal pruning does not only reduce the pruning cost, but also has the potential to increase the yield although ripening can be delayed for a high rain risk. While these decisions were motivated by costs saving needs, growers who have chosen one of these routes need to pay attention to the general health of their grapevines, as well as being attentive to crop management to sustain production for the following years.

Spur Pruning

Image 1. Spur pruned Thompson Seedless vines at beginning of this year near Fresno

To obtain a meaningful yield, growers cane prune traditional raisin varieties, e.g., Thompson Seedless, Fiesta and Selma Pete. This is because these varietals have low fruitfulness on basal buds, while buds farther up the cane have more clusters (Cathline et al. 2020). Cane pruning is also necessary for raisin mechanical harvest, e.g., continuous tray and DOV raisin. Spur pruning by hand does reduce labor cost by 35% in comparison to cane pruning (University of California Sample Cost for Raisin and Wine Grape in 2016). Pruning to a 2-bud spur will eliminate crop yields in the current season. No crop will mean less fertilizer need in the coming season, as harvest is the main loss of nutrients out of the vineyard. No crop could also allow for a longer spray interval, in comparison to a normal production year.

Growers still need to monitor the vines through the entire season, even if there is little to no expected crop. Healthy, photosynthetically active canopy are needed to produce strong canes and store carbohydrates in the permanent vine structures, such as trunk and roots to sustain the following year’s canopy growth. Early season carbohydrate supply also directly impacts the yield through bud inflorescence primordia formation. Therefore, mildew disease management is still necessary even for spur pruned raisin vines, although a longer spray interval might be enough to control the foliar mildew. Growers should also watch the water and nutrient status of the vines with the goal of producing strong vines and meaningful crop for the next year.

Due to little or no crop resulted from spur pruning, healthy vines tend to be more fruitful the following year. Growers who decide to go with spur pruning this year may need to adjust pruning severity, water, and fertilizer next year to avoid over-cropping and delayed maturation.

Summary:

1. Maintain a healthy canopy even with no expected yield to sustain the following season’s crop.

2. Manage vines starting this dormant season for a potentially big crop next year with pruning, water, and fertilizer.

Minimal Pruning

Minimal pruning entails hedging the dormant canes close to the vineyard floor. Minimal pruning has been studied in Australia on wine and Sultana grapes. These studies confirmed that minimal pruning increased the number of clusters, but reduced cluster size and berry size compared to spur or cane pruning. This overall led to improved color of wine grape, but delayed maturation. In addition, mechanical crop thinning was applied on minimally pruned vines to reduce crop load. Thinning advanced maturity, and further improved organic acids and color (Clingeleffer 2009).

Image 2. (Left) Minimal pruned Thompson Seedless vines at budbreak this year near Kerman. (Right) Minimal pruned Thompson Seedless vines at bloom this year with a larger number of clusters near Kerman.

Figure 1. Correlation between pruning level and raisin yields and data were averaged from three years between Fresno and Madera. From Christensen et al. (1994).

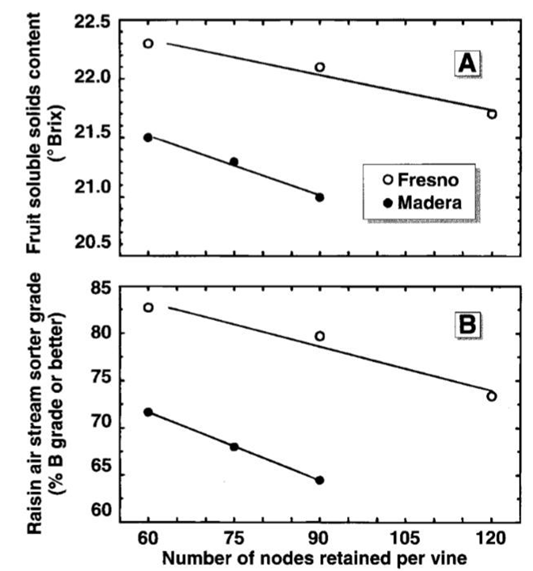

A pruning severity study led by Christensen et al. (1994) produced similar results; more nodes retained after pruning led to higher yield. Specifically, for each additional 15- node cane raisin yield increased by 0.36 lbs/vine for Thompson Seedless (Figure 1). However, more nodes retained also lead to lower Brix at drying and poorer raisin quality (Figure 2). Specifically, an additional 15-node cane decreased soluble solids by 0.23 Brix and 0.36 Brix and lowered the B&B better by 1.5% and 2.6% at Fresno and Madera, respectively.

More recently, a cane length study (Cathline et al. 2020) confirmed the similar results for Thompson Seedless when long canes were retained. However, long canes or more nodes/vine did not increase the raisin yield for new varietals, e.g., DOVine, Selma Pete and Fiesta. Long canes or more nodes/vine did delay the ripening and had the risk to lower the raisin quality across all the varieties, especially the clusters at the apical nodes.

Figure 2. Correlation between pruning level and harvest berry soluble solids (A) and correlation between pruning level and harvest raisin quality (B). Data were averaged from three years at Fresno and Madera. From Christensen et al. (1994).

Therefore, minimal pruning or retaining more nodes after pruning has the potential to increase crop for Thompson Seedless, though maturity is likely to be delayed. As for raisin growers, since heavy crops are associated with slow ripening; that also means a higher risk of rain during drying. Minimal pruned vines also tend to have an earlier and larger canopy than normal cane pruned vines, thus require more water input as well as nutrients. High disease pressure and inadequate spray coverage are also possible due to a large and dense canopy.

Management measures to consider with minimal pruned vines:

Supply adequate water.

Watch vine for nutrient deficiencies and fertilizer. Improve spray coverage or short spray interval.

Foliar K or ethephon spray after veraison.

Apply K and ethyl oleate with the spray-on-tray (SOT) treatment.

The first two measures aim to support the large canopy and yield. The third aims at dealing with higher mildew pressure in a denser canopy. The last two target at advancing the raisin drying to facilitate either DOV raisins or traditional tray dry raisins to avoid rain risk. K2CO3 is the most widely used form of K for the drying emulsions, and the foliar spray might contain lower rate of K2CO3 and ethyl oleate, like 2%, while a higher rate might be needed for SOT raisins. More information about raisin drying emulsions can be found at Raisin Production Manual 2000. UC ANR Publication #3393.

Reference:

Cathline, K.A., Zhuang, G., Fidelibus, M.W. 2020. Productivity and Fruit Composition of Dry-On- Vine Raisin Grapes Pruned to 15- or 20-Node Canes on an Overhead Trellis. Catalyst, DOI: 10.5344

Christensen, L. P., Leavitt, G., Hirschfelt, D., Bianchi M. 1994. The Effects of Pruning Level and Post-Budbreak Cane Adjustment on Thompson Seedless Raisin Production and Quality. Am. J. Enol. Vitic., vol. 45.

Clingeleffer, P. R. 2009. Influence of Canopy Management Systems on Vine Productivity and Fruit Composition. Proceedings of Recent Advances in Grapevine Canopy Management, July 16, Davis, CA.

Fidelibus, et al. 2016. Sample Cost to Establish A Vineyard and Produce Dry-On-Vine Raisins on Open Gable Trellis System. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources https://coststudyfiles.ucdavis.edu/uploads/cs_public/43/85/4385b69b-078a-43d9-8f39- 6ac149688fb5/16dovraisinsogtsjvfinaldraft111716.pdf.

Verdegaal, et al. 2016 Sample Cost to Establish A Vineyard and Produce Wine Grapes – Cabernet Sauvignon Variety. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources https://coststudyfiles.ucdavis.edu/uploads/cs_public/a8/4a/a84a16ba-4971-4348-8a55- 5f2f6f372134/2016grapewinelodifinaldraftmay192019.pdf.